From the Ground Up

Author

Published

1/13/2023

In 1913, Traverse County formed Minnesota’s very first county Farm Bureau, following the lead of other counties throughout the country that had started to organize associations to promote the farming industry and showcase the crucial role farmers played in their communities.

Within five years, there were Farm Bureaus in every agricultural county in Minnesota, and in 1919, it was suggested that they band together to form a state association to address the problems and challenges that went beyond the local level. On Nov. 8, 1919, the Minnesota Farm Bureau Federation was officially founded with 16,475 members from 45 counties throughout the state.

At the time, one of the biggest issues facing farmers was the aftermath of World War I. During the war and the years following, the need for agricultural products in war-torn countries that couldn’t produce their own supplies was high, leading to a period of prosperity for American farmers. Backed by long-term loans encouraged by the U.S. government through legislation like the Federal Farm Loan Act, farmers invested in land, tractors and other equipment to ramp up production.

But as Europe began to recover, the need for U.S. agricultural products disappeared. This surplus of goods at home caused farm prices to collapse, and with real estate values plummeting due to less demand for land, many farmers struggled to repay their loans. By 1932, 2,866 Minnesota farmers declared bankruptcy.

It wasn’t until the late 1930s, after Congress passed several farm relief measures, that the farm economy finally began to improve. At that point, the MFBF was nearing its 20th anniversary of being an advocate for farmers—a reputation that, for decades to come, would precede the organization. MFBF was campaigning to bring electricity to farmers in the 1930s, lobbying for meaningful statewide tax reform in the 1960s and fighting the foreclosure of countless farms in the 1980s, when farmers couldn’t keep up with soaring interest rates (see page 18 for a more detailed timeline of MFBF milestones).

That determination of leadership to continue advocating for its member farmers—while no doubt facing these challenges on their own farms—is why the MFBF still stands today. As the organization celebrates its 104th anniversary in 2023, learn more about its past, support its present and celebrate its future.

Agriculture Leader

Today, the MFBF is nearly 30,000 members strong, comprising 78 county Farm Bureaus, making it the state’s largest agricultural organization.

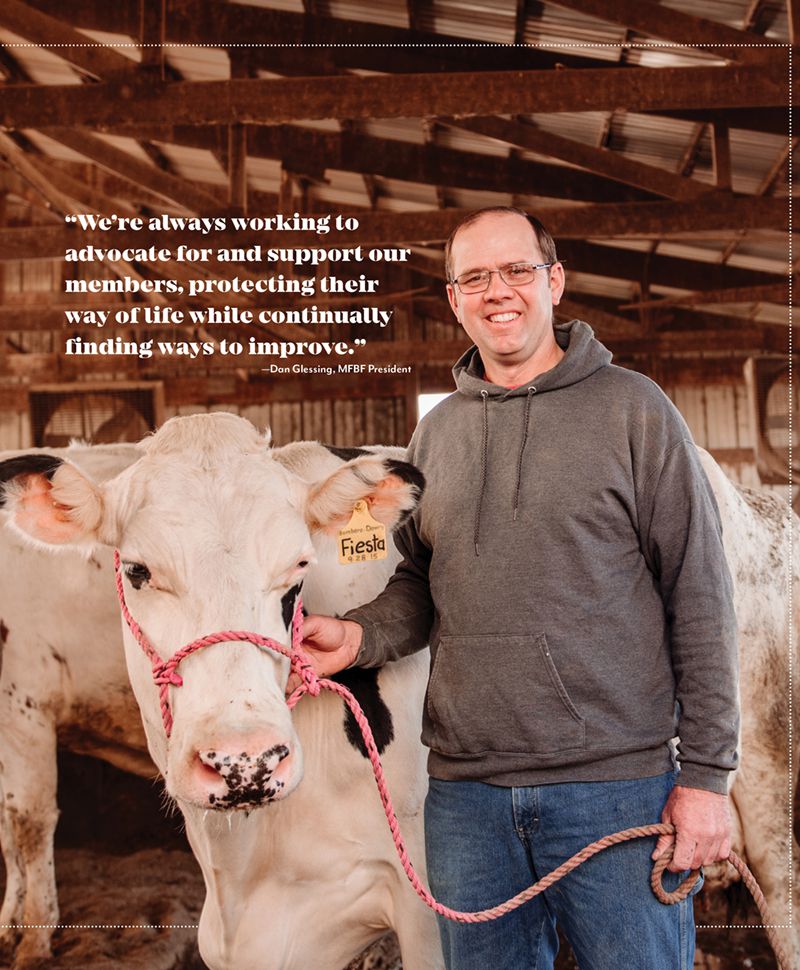

“We’re always working to advocate for and support our members, protecting their way of life while continually finding ways to improve,” says MFBF President Dan Glessing.

And while Farm Bureau’s work is far reaching, the organization focuses its programming into three avenues: membership engagement, agricultural awareness and grassroots advocacy.

Through engagement opportunities, members have the opportunity to grow personally and professionally in their own way. One specific way is the Young Farmers & Ranchers Program, where 18- to 35-year-old members can participate in programming to prepare them for leadership roles within the MFBF and other agriculture organizations in their communities. (Get to know a couple of these YF&R through the Q&As on page 16).

Agriculture awareness programming is designed for both members and consumers. Farm safety, educational materials and recognition for Century and Sesquicentennial Farms engage those involved in farming. County Farm Bureaus are continually connecting with their communities to raise awareness about agriculture, building understanding about where food comes from and how it got there. MFBF also partners with Ag in the Classroom, and has a large presence at the Minnesota State Fair.

MFBF is well known for its longstanding grassroots approach to policy development, surfacing and addressing the issues most important to its members. As a trusted voice with elected officials and leaders when it comes to agriculture and rural topics, the organization’s members are consistently working at the state and national levels to bring awareness to and effect change on key issues in agriculture.

“You can see from the work they do that each county Farm Bureau has its own reasons for being a part of MFBF,” says Glessing. “Some are really strong on policy, some are really strong on YF&R, some are really strong on outreach. There’s no right or wrong answer. Your membership is doing what you want it to do, and that’s the beauty of being part of a grassroots effort.”

Planting Seeds for the Future

While MFBF has been a staple of the state agricultural community for more than a century, the organization is far from stuck in the past when it comes to embracing new methods of and tools for farming, or getting the next generation involved.

While MFBF has been a staple of the state agricultural community for more than a century, the organization is far from stuck in the past when it comes to embracing new methods of and tools for farming, or getting the next generation involved.

New and emerging agriculture is a fast-growing and continually evolving sector. Glessing believes MFBF can support that group and those looking to begin their agriculture journey by offering a network and resources because, as all farmers know firsthand, “it’s hard to get started.”

“Some farmers say that if you’re not producing corn or soybeans, you’re not farming. My opinion is, if somebody wants to have a small food plot for the neighborhood, that’s farming. You’re still producing food for consumers,” says Glessing, whose family farms in Waverly. “The pride they have is no different than the pride I have when I see a combine coming across the hill or watch a calf being born. My hope for the future is for people to farm in whatever avenue and whatever aspect they want.”

Perhaps the biggest change from years past—and opportunity for the future—has been the evolution and adoption of technology to make farming practices faster and more efficient. Computers in tractor cabs, GPS, drones and satellite images can all be used in precision agriculture to increase and enhance crop production, or “crop per drop.” Self-driving autonomous tractors can perform without an operator in the cab, allowing farmers to focus on other tasks.

“We’ve seen light years of change in the last 15 years on the technology side, and part of me wonders if we’ll see the same kind of change in the next 15 years,” Glessing says. “That’s the exciting part. Where are we going to be? My grandpa would never have thought we’d be farming the way we’re farming. What will I be saying when my kids are farming? When I get to retirement age, what kind of changes are they going to be adapting to stay relevant and be successful? Only the future knows that.”